I have a habit of embarking on very intense side projects that consume all my free time.

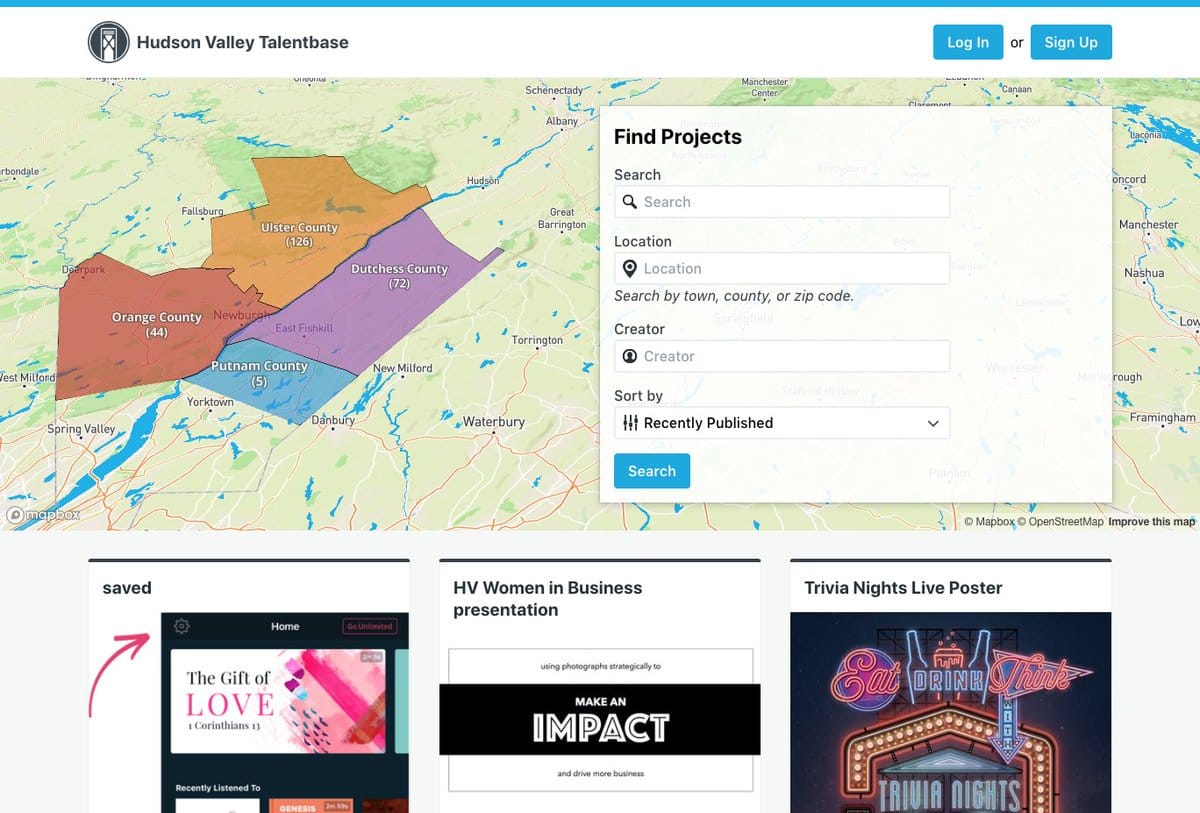

The first was Hudson Valley Talentbase — think Behance or Dribbble, but specifically for the Hudson Valley. The idea was strong, but ultimately lost momentum due to a truth that’s obvious in hindsight: a community built on people sharing their work will ultimately favor work that happens on a short timescale. If you’re a novelist and you write one book every two years, does that mean you only post once every two years? It’s hard to sustain a vibrant community built that way.

My second project like this was Creative Hudson Valley, an online publication where I interviewed people doing interesting work in the region. This solved one problem but added another: on one hand, the additional editorial control meant that the site could showcase people doing the highest-quality work no matter the type or timeframe of output. On the other hand, it required substantial labor from me to keep it running.

My third project along these lines, after Hudson Valley Talentbase and Creative Hudson Valley were both sunsetted, is ConnectHV. It’s similar to Talentbase in that it’s a software product in which people can create their own profiles, but its approach is orthogonal to Talentbase’s — instead of focusing on the work, it focuses on the people.

Anyone with a Hudson Valley zip code can create a profile, upload some work, write some words, and make themselves publicly searchable. The database is rich enough that people can find each other easily: you can search for things like designers in Ulster County or filmmakers in Poughkeepsie and return a list of people who meet the criteria you’re looking for. I’ve spent a couple of years revising the value proposition, but the phrasing I’ve settled on is this: ConnectHV helps you to find your next coworker, contractor, cofounder, or creative collaborator.

The common thread among all these projects, of course, is the Hudson Valley. It’s where I was born and raise and always planned to return. The Hudson Valley is large and spread out — in the 100-mile corridor between New York City and Albany, there are 11 counties and over 2 million residents.

The creative energy here is astounding, but it’s also hard for people to find one another. Let’s say you’re an engineer looking for a designer; if you live in a creative center like Manhattan or San Francisco, you can walk into the nearest Blue Bottle Coffee, throw a rock, and hit someone qualified to be your cofounder. Not so in a place as geographically diverse as the Hudson Valley.

We need a network that’s as distributed as our geography. We need an engine for fostering creative serendipity.

At least that’s my thesis. The communities in creative hotspots like Kingston, Beacon, and Poughkeepsie are already connected. But how do we build connections among those various communities, so that a filmmaker in Beacon can find a composer who lives in Rhinebeck, or a small business owner in Poughkeepsie can find a CFO-for-hire in Kingston?

That’s what I’m aiming for with ConnectHV.

Imbuing software with a sense of place

The easiest way to build a directory would’ve been to either use an off-the-shelf software product as-is, or to take some open-source platform like WordPress and theme it to be some approximation of what I wanted.

Neither of those approaches felt fully authentic to my vision, though. I’m a big believer in “eating your own dogfood” (or “drinking your own champagne,” as some prefer). If my goal is to showcase and connect the incredible work being done in the Hudson Valley, the platform itself should be incredible work done in the Hudson Valley.

So I decided to start from scratch. Every pixel and every line of code has been conceived from scratch in the Hudson Valley. By happy accident, even the underlying coding framework I’m using has Hudson Valley ties — Laravel, a PHP framework, was developed under the auspices of a Poughkeepsie-based company.

(A “coding framework” is a set of common functions and boilerplate conventions that abstract away common tasks, like interfacing with a database or rendering content to the screen. They enable developers to focus on the parts of their project that are unique, rather than those that are common to every software project.)

Even so, I’ve grappled with how to make ConnectHV an authentically Hudson Valley project.

Different ways of understanding “software with a sense of place”

The materials with which physical objects are made are imbued with specific geography. Rock and marble contains traces of the place it was brought out of the earth. Metals contain the story of their environment. Even the most abstract physical materials, such as plastic, can’t escape the fact that they were produced in a place out of raw materials that were produced in a place.

Food contains even more geography. Wine from different regions has completely different qualities, informed by the chemical content of the soil and the bacteria present in the place where it’s fermented. (This is the eponymous ”terroir” in “digital terroir.”)

Software has no such sense of geography. We speak in terms of pixels and code, but there are abstractions on top of the underlying reality: software is a series of instructions conveyed in 1s and 0s (really, billions of tiny switches being set to “on” or “off” inconceivably fast), resulting in electrons firing onto a flat surface to produce patterns of light.

Pixels don’t have a sense of place. They are not made of fibers produced from trees that grew in a particular forest; they are not written in ink whose origin can be traced.

Code doesn’t have a sense of place. It might have styles and conventions that are particular to the programmer, but not to the degree that literature from Russia differs from literature from Argentina. There are far fewer popular programming languages than spoken languages, and fewer ways to convey the same idea than in the written word.

A digression: does software really need to have a sense of place?

No, of course software doesn’t need a sense of place, any more than I want an iPhone made in one place to be different than an iPhone made in another place.

By day, I work on design systems at a large global company. “Design systems” are a way of keeping interfaces consistent and high-quality — essentially, a library of components and conventions that unify work done by various teams at the company.

Do we want the software our company makes to have regional variations, or even variations based on the personalities and preferences of its engineers and designers? No! Do we want our software that’s used by people all around the globe to feel rooted in a particular region, or should it have an approachable neutrality that makes it accessible to anyone anywhere?

In other words: the personality of software tends to come from the software itself, without being informed by its place of origin, because software doesn’t really have a place of origin. Its “place of origin” is the web — it’s built out of non-regional raw materials by people whose skills are aggregated from forbearers all around the world developing a common “digital production” culture with little regard for borders, answering Stack Overflow questions from people halfway across the world and learning from blog posts written anywhere and everywhere.

Three takes on “a sense of place” for software

In my current thinking, there are three possible ways that software can have a sense of place:

💅 The superficial way

The software is non-regional, but it has a regional ”coat of paint.” This is the most obvious, least satisfying, interpretation of digital terroir. The website for the New York State DMV feels like a New York website because it has a little picture of New York State on it. If you swapped out that picture for a picture of Montana, though, would anyone be able to tell it wasn’t actually a website from Montana?

🧱 The foundational way

The underpinnings of the software are regional. Theoretically, if the software were written in some regional style using a regional programming paradigm (is there such a thing?) and design language (there is such a thing, but just barely), it would feel like the place where it was written. I suspect it would feel forced, though, and perhaps unnoticeable to most observers.

🌱 The realistic way

We imbue the design and content of the software with regional characteristics, while acknowledging that software itself might not have regional characteristics at the foundational level.

This is the version that seems most realistic to me right now. I don’t know that I can imbue ConnectHV’s code with Hudson Valley flavor, but I can nod to the Hudson Valley through the design and content of the site. I can put some of my own values, informed by three decades of life in the Hudson Valley, into the site, both consciously and unconsciously. I can nudge users towards behaviors that align with Hudson Valley attitudes and folkways. I can imbue the site with regional design reinforced by responsible code.

I suppose this is all reliant on understanding what makes a place feel like that place. In the original ”Digital Terroir” talk I gave at CatskillsConf 2018, I phrased it like this:

When I think of the Hudson Valley, I think of places like the Ashokan Center. I think of towns like New Paltz and Beacon and Rhinebeck, which each have their own personality but still share the values of the Hudson Valley. I think of the places to hike, and the places to eat, and the farmers’ markets and independent stores.

The Hudson Valley is about small farms, slow food, and good neighbors. It’s about doing good work, but avoiding the mentality of “growth at all costs.” The pace is a little slower here than in New York City, but thanks to the easy train access, we still have the cultural benefits.

And what does this look like, practically? Again from 2018:

The things we make can be imbued with the character of the Hudson Valley. We can make software with breathing room, both in the design and in the user behavior it encourages. We can reject the idea of “growth at all costs” and instead build products that promote our users’ wellbeing. We can design and program things in a way that respects work-life balance, and helps people to thrive, for no other reason except that they’re people, and people have infinite worth. We can make software that shares our values, knowing that our values are influenced by the place that we’re planted.

I don’t find that answer satisfying anymore. I don’t know that I did then, either, but a conference talk needs an ending that sounds nice. The truth is, that description could apply to lots of places, not just the Hudson Valley.

And so I’m left with a lead on what it looks like to imbue ConnectHV with the spirit of the Hudson Valley, but still more questions than answers.

Here’s what I need to pursue:

- What makes a place feel like a place?

- What makes certain places feel “thick“ — lived in, organic, historic — and other places feel “thin” — superficial, unrooted, transient?

- What makes software distinctive from other media? How do other media find themselves rooted in a place-and-time (how could anyone but Kerouac write Kerouac? Or anyone but Dostoevsky write Dostoevsky?), and how does that manifest with software?

And, perhaps most importantly: should we want any software to have a sense of place, or do we want it to be completely transparent so we can use it quickly and then get back to our lives?